Free Will Libertarianism

Those disturbed by the implications of hard determinism might find solace in libertarianism, the view that some human actions are free and not causally determined. I will explain libertarianism as best as I can, but before I do so I must admit that I don't understand it. This might be a limitation on my part, or it may be because libertarianism is incoherent--which is the most common objection to it. Anyway, I have lots of practice trying to explain things I don't understand, so I'll go ahead and try.

Let's start with the claim that some actions are not causally determined. I get this part. Libertarians think that sometimes humans act in ways that are not determined by the laws of nature. This means that at least one time in human history, there was a human who performed an action, but who--as far as the laws of nature and the conditions of the universe at that moment were concerned--could have performed a different action.

"Water's a little cold; let's go back."

"Nah, guys, this'll lead to some bad business writing in a few thousand years."

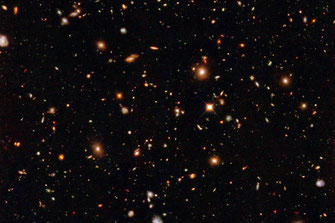

While it would not be convincing to philosophers like Leibniz, who held that everything that happens must have a determining reason, and it would have been surprising to many prior to the revolutions in physics in the 20th century, many of us are now comfortable with the idea that things can happen without a determining cause. For example, in the double-slit experiment, whether a photon goes through slit A or slit B is not determined by anything. Photons' lives are not "lines that nature commands them to inscribe upon the surface of the earth." So just as we can make sense of a photon behaving without a determining cause, we can make sense of a human behaving without a determining cause. (I have just explained the possibility of humans' not being determined by analogy to quantum behavior. This is not at all to say that quantum indeterminacy leads to human freedom, as many people have suggested. More on this later.)

But there are at least two problems with seeing randomness as the road to understanding free human actions. I will call the first the character problem. Often, the people we admire the most act in very consistent ways. We don't thereby think that these people are less free. We think they have a good character and we trust their actions to come from their character. If a person acts anything like a photon, we don't want to be anywhere near them.

Unless they're three.

I will call the second problem the control problem. Libertarians want to say that human actions are not only not causally determined, but free. Whether they happen is up to the agent who performs them. And random actions are not up to the person who performed them. If a double-slit experiment were to be hooked up to my brain in such a way that if the photon went through slit A, I would raise my right arm, and if the photon went through slit B, I would raise my left arm, then the resulting behavior of my body, while not causally determined, would not be free.

So while the idea of an event happening without causal determination is clear, libertarians have to give a further explanation of human freedom. They must say how the lack of causal determination is consistent with often very predictable behavior stemming from our characters, and how we can control actions that are not determined.

As Timothy O'Connor observes, we can't solve the character problem by thinking of our character as statistical laws governing our actions, because we run right into the control problem. We can set up an experiment such that there is a 93% chance that the photon will go through slit A. Similarly, we can conceive of my character as giving me a strong disposition to ordering vanilla ice cream, such that I will do it 93% of the time. But even with this bias towards vanilla, if whether I order vanilla on any given occasion is as random as a photon with a 93% chance of going through a given slit, then it isn't up to me whether I do so, and it isn't free.

The character and control problems pull us in opposite directions. My character consists in some of my beliefs, desires, and dispositions to act. For an action to be in line with my character, it seems like it should be strongly influenced by them. The stronger the influence, the closer the connection to my character. But the stronger the influence, the more it looks like my beliefs, desires, and dispositions to act are determining my behavior, and that I am not in control.

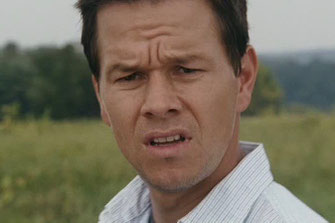

Here's another way to see the problem. If I decide to order vanilla, the decision results in the firings of many neurons, which are material objects, followed by activity in much larger material objects like the vagus nerve and my vocal cords. According to libertarians, at some point in my neural processes, things could have gone way one or another. I was the one who controlled which way, which means that I controlled how all of this matter behaved. According to libertarians, my choosing vanilla was not determined by anything prior, yet somehow reflects my character, and results in the creation and direction of electricity from pure will.

I would not have guessed that someone would think to impress from the display of a thoroughly common ability.

Roderick Chisholm referred to this ability to make matter behave one way rather than another, without prior causal determination, as akin to the power to create from nothing, to being a prime mover. We come yet again to the idea that our ability to decide is divine. You might think that Chisholm was saying this in a critical fashion--for it is absurd to think that we have the power of God! But no, remarkably, Chisholm was a libertarian, one with a clear view (in my opinion) of how strong an assertion the view really makes.

Copyright 2019 by Sam Ruhmkorff